Donald Trump’s approach to economic policy follows no consistent set of principles. Although he has enacted measures traditionally associated with the right, such as cutting taxes for the wealthy and rolling back regulations, these choices appear driven less by ideology than by transactional self-interest. Tax cuts reward donors and business allies, while deregulation satisfies powerful interest groups and reflects a hostility toward policies designed to serve the public good.

This governing style evokes comparisons to Richard Nixon. Particularly, because of Trump’s readiness to intervene directly in the economy, yet the similarity is superficial. Nixon’s controversial wage and price controls were enacted through legislation and institutional processes. Meanwhile Trump relies on declarations and pressure tactics, expecting compliance without legal grounding.

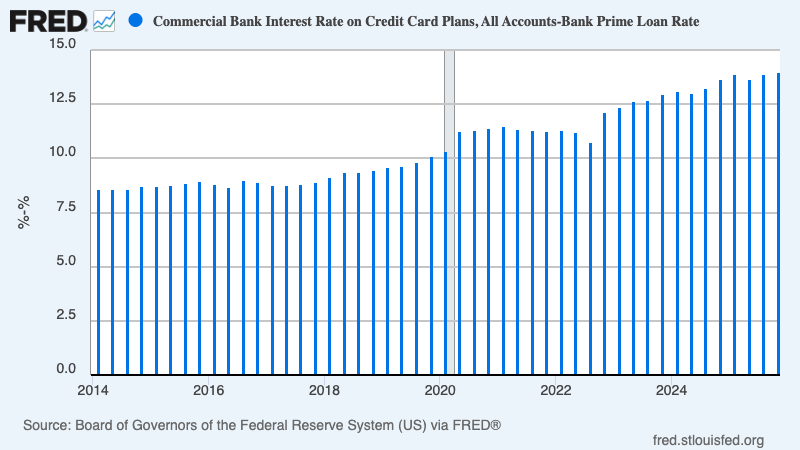

That contrast is especially clear in Trump’s announcement of a one-year cap on credit card interest rates. The move appears timed to blunt electoral losses rather than to address consumer harm in a durable way. While there is a legitimate economic argument for curbing credit card rates. This is due to the sharp rise since 2019 and the exploitative business practices that trap vulnerable borrowers, so the proposal clashes with Trump’s record. His administration previously moved to cripple the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the federal agency tasked with protecting consumers from predatory financial practices.

Political Theater Over Consumer Protection

The contradiction undermines any claim of genuine concern for households burdened by debt. Without legislation passed by Congress, a presidential pronouncement cannot impose a binding interest-rate cap. Republicans are unlikely to support such legislation, and Trump has shown little interest in pursuing it seriously.

The only meaningful path to consumer protection would be restoring and empowering the CFPB, allowing it to resume enforcement against abusive lenders under existing law. Without that step, the interest-rate cap functions as political theater rather than policy. The pattern fits a broader tendency to substitute bluster and symbolic gestures for governance, with the expectation that spectacle will outweigh substance. An expectation that may no longer hold with voters.

Reference

Krugman, P. (2026, January 14). Donald Trump, Would-Be Price Controller. Paul Krugman. https://paulkrugman.substack.com/p/donald-trump-would-be-price-controller?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=59ocs7&triedRedirect=true