Introduction

Calls to “bring manufacturing home” have echoed across American politics for generations. Yet, the push has intensified in recent years as geopolitical tensions rise and global supply chains feel increasingly fragile. Recent policy shifts, especially tariff-driven strategies, have promoted a vision of industrial revival. Promising factories, jobs, and technological dominance firmly rooted on U.S. soil. High-profile corporate investment announcements helped create an aura of national reindustrialization. Yet broad structural data tells a different story. Supply-chain exposure is shrinking in some directions but deepening in others, challenging assumptions about reshoring and raising uncomfortable questions about what “economic self-sufficiency” really means.

The Facts

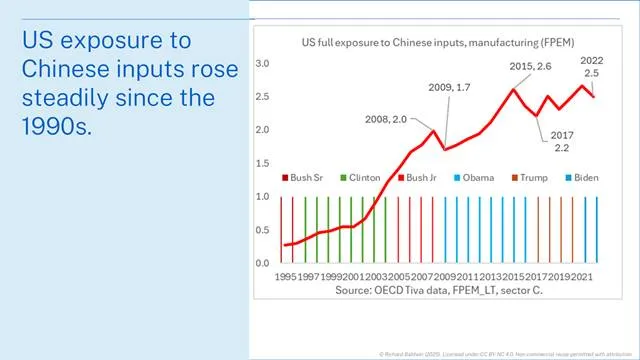

Despite headlines about massive U.S.-based investments in semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, and data infrastructure, aggregate exposure to Chinese industrial inputs has not declined. Since the 1990s, the share of U.S. manufacturing inputs ultimately sourced from China climbed from almost zero to roughly 2.5% by 2022. Importantly, the increase did not slow after the imposition of large tariffs beginning in 2018.

Even with reshoring rhetoric in full swing, U.S. manufacturers continue relying on Chinese upstream components embedded deeply throughout global production networks.

What is the FPEM measure of foreign supply-chain exposure?

FPEM, adopted by the OECD, provides a comprehensive look-through measure that accounts for the full architecture of global supply chains. Instead of tracking only direct imports of parts from China, the metric captures Chinese components embedded in goods imported from third countries. For example, Chinese parts inside German auto components or Taiwanese electronics. Calculating FPEM requires extensive global input–output data, so available numbers run only through 2022.

While the percentages are small relative to total U.S. input use, the trend remains unmistakable. Chinese exposure grew for decades and shows no sign of falling, even as domestic subsidies (CHIPS, IRA) and new tariff waves attempt to shift the balance.

Reshoring is real, decoupling from China is not

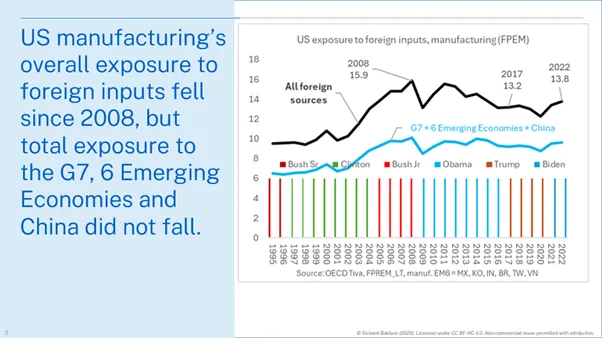

Overall foreign exposure declined after the Global Financial Crisis, dropping from around 16% in 2008 to roughly 13–14% in the mid-2010s. U.S. manufacturing did become less globally dependent, but this decline masked a pivotal shift in sourcing patterns.

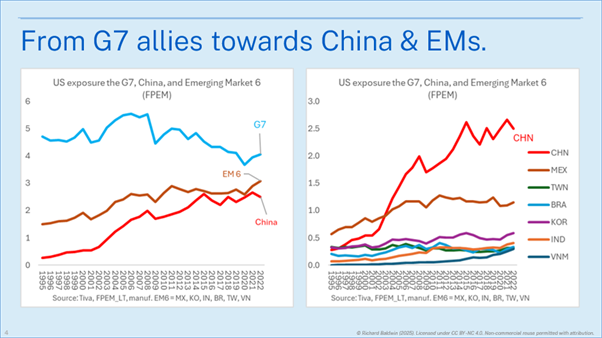

Exposure to traditional allies in the G7 steadily fell, while sourcing from China and rapidly industrializing economies such as Mexico, Korea, India, Brazil, Taiwan, and Vietnam steadily rose. China gained the most ground by far, reaching nearly 3% of total inputs by 2022.

In effect, supply chains became less global but also less allied, drifting away from long-standing partners and toward strategic competitors. Instead of friend-shoring, the pattern resembles reverse friend-shoring.

Summary and Concluding Remarks

The reshoring narrative contains a paradox. High-profile domestic investments coexist with an industrial base that remains deeply intertwined with China. Reduced global exposure has not translated into reduced Chinese exposure. In fact, dependency has become more concentrated geographically, suggesting that resilience may be far more limited than political messaging implies.

Even if specific technologies or strategic sectors manage to localize production, the broader industrial web, built over decades of integrated international supply chains, cannot be unwound quickly. The “Omelette Problem” captures this reality. Once the inputs of U.S. industry were mixed into a global system, separating them back into discrete national sources became nearly impossible.

Closing Remarks

The United States has successfully reduced dependence on the world at large, yet dependence on China has intensified. Any realistic policy debate—whether oriented toward genuine decoupling or toward a managed coexistence—must begin by acknowledging that fundamental tension. Only then can durable strategies for supply-chain security, industrial resilience, and geopolitical stability take shape.

Reference

Baldwin, R. (2025, December 5). Is US Friend-Shoring in reverse? Richard Baldwin Substack. https://rbaldwin.substack.com/p/is-us-friend-shoring-in-reverse?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=59ocs7&triedRedirect=true